Love vintage and antiques? Visit CollectorsWeekly.com, a resource for people who love antique and vintage stuff. It's a good place to explore and learn and benefit from the knowledge of collectors everywhere

What’s there?

- In-depth information (including top eBay auctions) on over 1,000 antique and vintage categories.

- News, commentary, and interviews on a daily blog.

- Thousands of local event listings (shows, auctions, museum exhibits, etc.).

- Show and Tell, where you can post and discuss your favorite finds with other collectors.

This article is typical of the site:

Barbed Wire, From Cowboy Scourge to Prized Relic of the Old West

By Ben Marks

Why would anyone pay $500 for a rusty piece of barbed wire? Well, if the 18-inch long specimen, or cut, is the only known example of the Thomas J. Barnes patent of 1907 (shown above), some folks might pay even more than that. In fact, for collectors of barbed wire, or barbwire as it’s also called, the past few years have been a veritable rust rush, as choice examples of rare wire that have been squirreled away for decades are entering the market.

This isn’t the stuff you see today by the side of the road, although the design of barbed wire has not changed that much in more than 100 years. What gets barbed-wire collectors excited are scarce examples of wire manufactured from 1874 through the first decade of the 20th century, when barbed wire was a multi-million-dollar business and everyone wanted a piece of the action.

The market for wire was driven by the new demand for fencing. Railroads needed to secure their newly laid right-of-ways (the last spike was driven in the transcontinental railroad in 1869), while ranchers were compelled to keep their livestock within property lines rather than letting them graze on the open range, which was increasingly being converted to farmland.

“There was a lot of resentment to barbed wire when it first came out,” says Harold L. Hagemeier, whose “Barbed Wire Identification Encyclopedia” is the hobby’s official guide. “The old cattlemen did not like it whatsoever. Until then, the ranges had been open. The ranchers sent out special crews to cut the fences and burn the posts, whatever was necessary. That went on for maybe 10 years, probably not even that long. Here in Texas, the governor finally signed a law making it a crime to cut fences, and a lot of other states did the same thing. It was barbed wire that caused those range wars.”

The virtues of barbed wire are touted in this 19th-century advertisement. Photo from the Ellwood House Museum.

“There was a lot of resentment to barbed wire when it first came out. The old cattlemen did not like it whatsoever.”While cattle ranchers sparred with farmers, the legal system was tangled by lawsuits over barbed-wire patents. Almost from the moment Jacob Haish and Joseph Glidden filed their first patents for barbed wire in 1874, the two men were squaring off in court. That same year, a hardware-store owner named Isaac Ellwood bought a 50-percent share in Glidden’s patent for $265. By the time the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Glidden’s favor in 1892 (his “Winner” design is used on most fences today), hundreds of patents for as many designs of barbed wire had been filed, and many more unpatented variations were on the market.

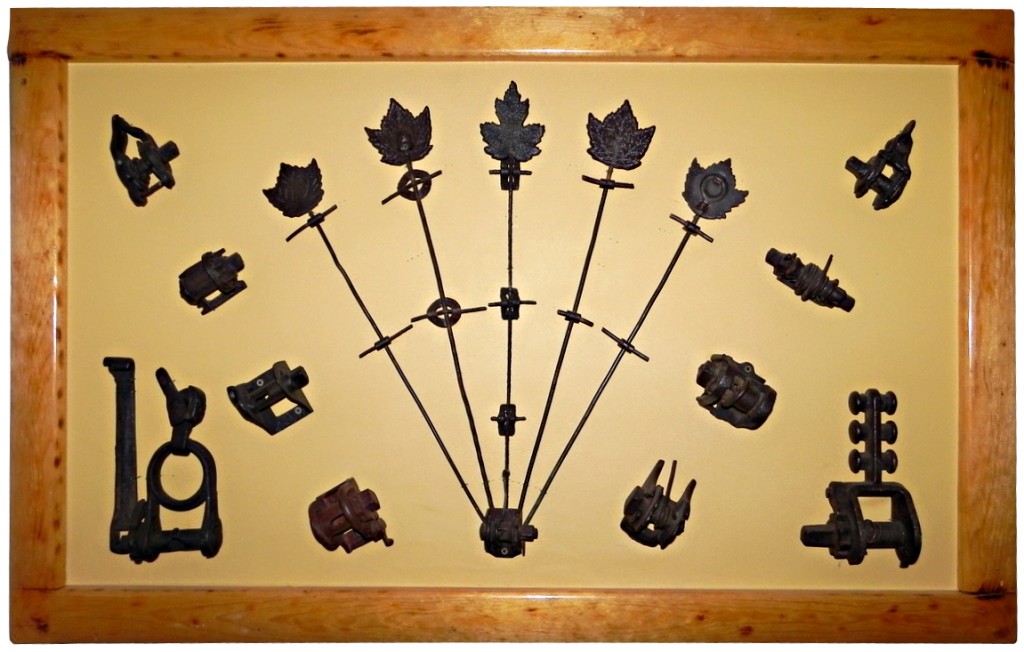

This legacy is of keen interest to people like Parker, who collect mostly 18-inch-long sections of wire, which are often mounted on boards so the twisted strands and barbs don’t get all tangled up. There were some 800 unique barbed-wire patents, and many more unpatented variations for a total of perhaps 2,000 types of barbed wire. Some feature wire barbs attached to single or double strands. Others sport stationary barbs or rotating rowels made of sheet metal in decorative shapes, from leaves to diamonds to stars. Some barbed wire isn’t wire at all, made instead out of ribbons of sheet metal that have been punctured or sliced to create nasty points.

Bronson Single Strand Double Loop Barb, patented in 1877 by Adelbert E. Bronson, Chicago, Ill. Photo by railman.

These days, Parker concentrates his collecting efforts on rare wire. “I like the figure barbs and some of the more complex bends,” he says. “It’s fascinating to me that they did this with the machinery they had back then. Now it’s easy, but in the late 1800s, the ingenuity of the machines they built to bend the wire and insert a barb was amazing.”

TheGateKeeper is another Show & Teller who credits his rural roots for his interest in barbed wire. “I grew up on a farm outside of Dallas,” he says. “Our farm was fenced with a strange-looking barbed wire with these metal plates in it. I cut myself and ripped my pants on that stuff for a long time. After I got married in 1961, we moved to the little town of Carrollton, also outside of Dallas. On our back fence were four different kinds of old wire that I had never seen before. That got me interested.”

Though his collection is not as large as Parker’s, TheGateKeeper has hundreds of pieces. “Right now I have 280,” he says. “I’m trying to keep my collection below 300 because I can only display that much in my office. Anything more than that I have to put in a box and hide somewhere. If I can’t display it, I don’t want it.”

“In a lot of cases, the patent attorney ended up owning the patent because the guy who came up with it couldn’t pay the fees.”For collectors like TheGateKeeper, maintaining a collection at a manageable size had not been too difficult because the number of rare pieces available to collectors had been limited. But in the last few years, he says, a couple of large collections have come onto the market. “People have passed on, gotten tired of it, or whatever. There’s some really neat stuff coming out of these collections, which makes it really tough to decide what to keep and what to get rid of.”

Most collectors specialize to give their collections focus. “I’ve concentrated my efforts on rare wire that has sheet metal incorporated into it somehow,” he says “either as a metal strip, ribbon, or a sheet-metal barb. I also like the wires that had wooden blocks in them as warning devices. Most wooden blocks burned up in grass fires, so those are pretty rare pieces of wire.”

TheGateKeeper is particularly enamored with ornamental wire, which, he says, was used to surround yards, cemeteries, and other areas where barbed wire was not necessary. “Ornamental wire was also used as stay wires between fence posts,” he says. “The shapes are really beautiful, and they’re an inch to two inches wide, which makes them very visible. Barbs could be added, but barbed ornamental wire evidently did not achieve wide acceptance.”

Star wire looks ornamental to contemporary eyes, but it was definitely used for containment and boundary fencing. “Utilizing sheet metal rather than wire as the barb medium made the barb more visible,” says TheGateKeeper. “In some designs it was also more humane because the barbs rotated. I’m also fascinated by all the symbolism in the designs. Each star shape has a different religious meaning.”

Railroad wire is another popular subset. “There were special ‘marker’ wires made for each railroad,” he says. “They’d change up the number of strands, twist a square strand with a round one for example, so that if the wire was stolen from a remote area, it would be easy to identify. Some people collect nothing but that.”

One of the most interesting subsets for barbed-wire collectors doesn’t even involve barbed wire at all. “The barbed wire was cutting up the animals,” says TheGateKeeper, “so they started making barbed-wire liniment. A whole new industry grew out of that. There are a ton of different liniment bottles from the 1800s that people collect. In fact, a collection of bottles was just donated to the Devil’s Rope Museum in Texas.”

There are numerous museums in the United States known for their association with barbed wire history, as well as institutions that collect the material itself. Naturally the three founders, if you will, of the U.S. Barbed wire industry are well represented. The Ellwood House Museum in DeKalb, Illinois, is devoted to the legacy of Isaac Ellwood, whose early investment in Joseph Glidden’s patent made him a rich man. Glidden’s more modest Homestead & Historical Center is located nearby. Jacob Haish’s legacy is maintained online by one of the great 19th-century inventor’s relatives.

To see good examples of wire, collectors routinely travel to the Kansas Barbed Wire Museum in La Crosse or the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. And then there’s Devil’s Rope.

Delbert Trew and his wife, Ruth, have been the public faces of the Devil’s Rope Museum in McLean, Texas (which is east of Amarillo near the Oklahoma border) since it opened in 1991. “The museum was put together by barbed wire collectors associations,” he says. “At the time, there were about seven or eight associations scattered throughout the Midwest mostly, and about 300 to 400 major collectors across the county. Most of them were getting old and wondering what to do with their collections. That’s where the museum’s collection really came from, those collectors.”

Back then Trew was not a barbed wire collector. “My deal was mostly tools,” he says. “But it did so happen that I lived near McLean where they decided to establish the museum. So my wife and I have been the local people that tend to everything. She’s been a treasurer and secretary all these years and I’ve been the museum’s supervisor.”

While the town of McLean did not have any particular historical association with barbed wire, it had other things going for it. “One of the priorities of the founding members was a building large enough that it could hold everything. And they wanted it to be on a major highway. It just so happened we had an empty brassiere factory right on old Route 66. They made brassieres for Sears Roebuck and Co., and had a hundred women working there for 20 years. After the factory moved out, to Mexico, I think, the owners of the building donated it to the city of McLean.”

This Hunt's Link variation was patented in 1877 by George G. Hunt of Bristol, Ill. Each link is 6.5 inches long. Photo by railman.

“Some of these guys have been collecting wire for 40 years; they’ve seen just about everything.”Tom Knapik, who teaches high school mathematics and posts his wire on Show & Tell as railman, could probably open his own small barbed-wire museum, but it wouldn’t be filled with just anything. “The Glidden ‘Winner’ was patented in 1874,” he says, “but to me, it’s one of the most dull, boring wires that has ever been created, even though it was the most successful. Probably the most outrageous and fantastic patent was the Thomas J. Barnes of 1907. It had flared barbs at the end of a tube that rolled and moved as an animal rubbed up against it. It’s an extremely rare wire. As far as I know, there’s only one 18-inch section that has survived the years.”

Knapik, who has maybe 120 pieces of wire in his collection, is always on the lookout for rare wire new to the collecting pool. For example, the collection of Robert Campbell, who wrote “Barriers: An Encyclopedia of Barbed Wire Fence Patents,” was sold a while back. “His collection contained the rarest of the rare,” says Knapik. “From what I’ve been told, he had riders who would go out and find new wires for his collection. He amassed one of the biggest collections ever.”

The Hart's Eight Point Spreader was patented in 1885 by Hubert Hart of Unionville, CT. From point to point, the barb length is 2.25 inches. Photo by railman.

“I fixed a lot of fence in my day. I didn’t like barbed wire then, and I still don’t like to fix fence today.”What’s an example of a rare wire? Well, that Barnes from 1907 to begin with. “Another is called the Utter,” says Knapik. “It was actually posted on Collectors Weekly. It was patented by a man from Cuba, New York, in 1887. It’s kind of like a rolling barb, but it rolls horizontally, not vertically like the Barnes. It’s a fantastic patent. From what I understand, maybe a dozen 18-inch-long specimens have been collected.”

The Barnes and Utter patents are just two examples of wire that were developed to keep the hides of livestock like cattle from getting torn up by static, inflexible barbs. “They started incorporating these unusual spinning designs that would poke rather than cut the animal as it was rubbing up against the wire,” says Knapik. “There was another one called the Greg’s patent that looked like a spring. It would retract if an animal pressed up hard against it. The idea was to herd them, not hurt them, to get them to change the direction. There was an understanding of what was happening to the animals, so inventors modified their patents to accommodate that.”

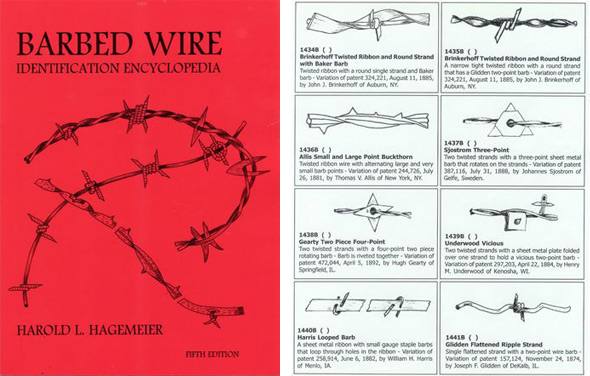

With so many patents and so many different types of wire, collectors like Knapik turn to various books to identify what they have and are about to buy. Most of them have their favorites, but all collectors use Hagemeier’s “Barbed Wire Identification Encyclopedia.” Featuring hand-drawn illustrations by Hagemeier’s wife, LaNell, the “Encyclopedia” was first published by Hagemeier in 1998. The book’s fifth and final edition came out in 2010, although a supplement was recently published, adding 108 newly identified specimens to the main book’s inventory of more than 1,700 different wires.

“You get to the point,” says Hagemeier, “where you think, ‘well, this is all of them’, and sure enough, somebody comes up with some more. A lot of the new wires are what we call variations. And I hate to tell you this, but there are also wires that I wouldn’t doubt are being made by some individual. I’m not accusing anybody, but I think that’s a good possibility.”

Naturally Hagemeier does what he can to keep fakes out of his encyclopedia. “There are about five or six collectors I contact when a new wire shows up,” he says, “to get their opinion, find out if they’ve ever seen one like it before, things like that. But that’s about as far as you can go. Some of these collectors have been collecting wire for 40 years, so they’ve seen just about everything that you could imagine. But you just got to make a judgment.”

The Matoushek Two Strand Star Barbis an exact execution of the patent description. Photo by railman.

In the process of collecting wires, Hagemeier noticed that a lot of his specimens were not identified correctly. So he started investigating the history of each wire as best he could, eventually organizing a group of four barbed-wire collectors to compare notes and figure out just exactly what they had. The result was the first book in 1998.

The Mouck Three to One Barb on Parallel Strands was patented in 1893 by Solomon Mouck of Denver, CO. Photo by railman.

Like all collectors, Hagemeier has his favorites. “I guess the wire I appreciate most is the Hodge Spur Rowel. It’s a two-strand wire with a barb that looks like a spur rowel on a little shaft that connects the two strands together. There are probably 20 unpatented variations on it.”

Although barbed wire was seen as a way to get rich quick, Hagemeier says it usually didn’t work out that way. “In a lot of cases, the patent attorney ended up owning the patent for the wire because the guy who came up with it couldn’t pay the patent fees, and whatnot. Often a wire would never get successful because it was too expensive to manufacture.”

In fact, many of the specimens prized by collectors are the samples submitted to the patent office. That’s all that was ever made, which means that’s all there is on the market today. Well, almost. “There are also, I’m sure, a lot of ‘replicas’. Let’s put it that way,” sighs Hagemeier.

“They started incorporating spinning designs that would poke rather than cut the animal.”The other big customers for barbed wire were the railroads. “The railroads had special wires, what we call railroad wires, which were a lot different. For instance, the wire strands might be oval rather than round or something special like that. People don’t realize that the development of a lot of this country would have been a lot slower if it hadn’t been for barbed wire.”

Today, the pace of barbed wire collecting is accelerating, although in the world of barbed wire, speed is a relative thing. Two of the most anticipated events are just around the corner. The first is the Antique Barbed Wire Society’s annual “Super Show,” which is hosted this year by the Colorado Wire Collector’s Association in Pueblo, Colorado, on September 23 and 24 and should be attended by as many as 500 people.

American Steel and Wire in DeKalb, Illinois, at Tenth Street looking northeast, DeKalb, circa 1901. Photo from Sycamore Public Library.

Still, even the dates chosen for the Super Show reflect the taut ways of the barbed-wire collecting community. “There’s been a little bit of controversy about when it’s best to hold the show,” allows Knapik. “Currently the shows are held on Friday and Saturday, but having it on Friday and Saturday seems to limit the number of families that can attend, and anybody who works can’t go on a Friday. They have to take time off, as I’ll have to. So that’s a little bit of an issue.”

The effectiveness of barbed wire on animals, dramatized and set in a circus ring. Photo from the Ellwood House Museum.

Creating this level of market predictability and price transparency is intended to keep the hobby accessible to as many potential collectors as possible. But some collectors will tell you privately that the clubby nature of events like the Symposium is not the sort of thing that’s likely to attract young people to the hobby. “Many of the older collectors are selling off their collections,” says one. “I don’t see a lot of new people coming up. I would hate to see the hobby just fade away.”

(Me) (Home)

0 comments:

Post a Comment